Summary

In a globalised world, economies, societies, and ecosystems are interconnected through multiple flows, such as trade links and global markets, financial interdependencies, and people’s movement. When climate events such as droughts and flooding occur in one part of the world, the consequences can be transmitted to other countries, regions, and continents. These cascading or cross-border climate impacts traverse national borders and jurisdictional boundaries, posing risks to countries and communities distant from the initial origin of impact. For example, in a region like the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), a combination of higher temperatures and water shortages could reduce agricultural yields, causing disruptions in food value chains and potentially leading people to move out of agriculture due to reduced opportunities. Consequently, increased rural-urban migration could strain public services such as water, energy, and food. These factors can exacerbate social unrest and regional instability, increasing migration towards Europe. Unsafe or illegal migration may create opportunities for organised crime (e.g., human trafficking) and entail various risks for migrants (e.g., accidents, violence, exploitation).

Agri-food systems are often crucial in risk cascades that connect climatic shocks with other challenges, such as disrupted economies or displacements. They also are a logical entry point for interrupting such cascades early on and for preventing climate shocks from propagating across domains (e.g., food, economy, health, security) and borders.

The strong likelihood of increasing impacts makes the question of how the European Union (EU) and its member states, in close cooperation with global actors, might build resilience in its surrounding regions an increasingly strategic political priority. Therefore, the overarching research question throughout this compilation is:

How can Europe respond coherently and effectively to cross-border climate impacts that originate in – or pass through – food systems?

This question is broken down into four sub-questions, as follows:

- How do the EU and the EU member states, individually, collectively, and through their cooperation with international organisations, contribute to mitigating cross-border climate impacts originating in agri-food systems in third countries with close ties to Europe (by supporting climate adaptation within these countries or regions)?

- What obstacles and opportunities exist for these actors to support the climate adaptation and resilience of agri-food systems in third countries? And, what will be the implications if limitations are not fully addressed?

- Which synergies or contradictions exist across policies in the domains of environment, development, security, migration, or trade concerning climate resilience of agri-food systems in third countries with close ties to Europe?

- How to improve policies and instruments to address cascading and cross-border climate impacts?

Conceptualising adaptation solutions to cross-border climate impacts

The inadequacy of responding to cross-border climate impacts is partly because traditional frameworks and policy processes on climate change impact, adaptation, and vulnerability define responses to climate change impacts as either a sectoral or local challenge, mostly within national borders. In other words, adaptation policies are mostly owned and steered in siloes at the national level. Consequently, they fail to capture and plan for interdependencies and cross-border climate impacts. However, climate change adaptation as a global challenge requires transnational and collaborative governance solutions.

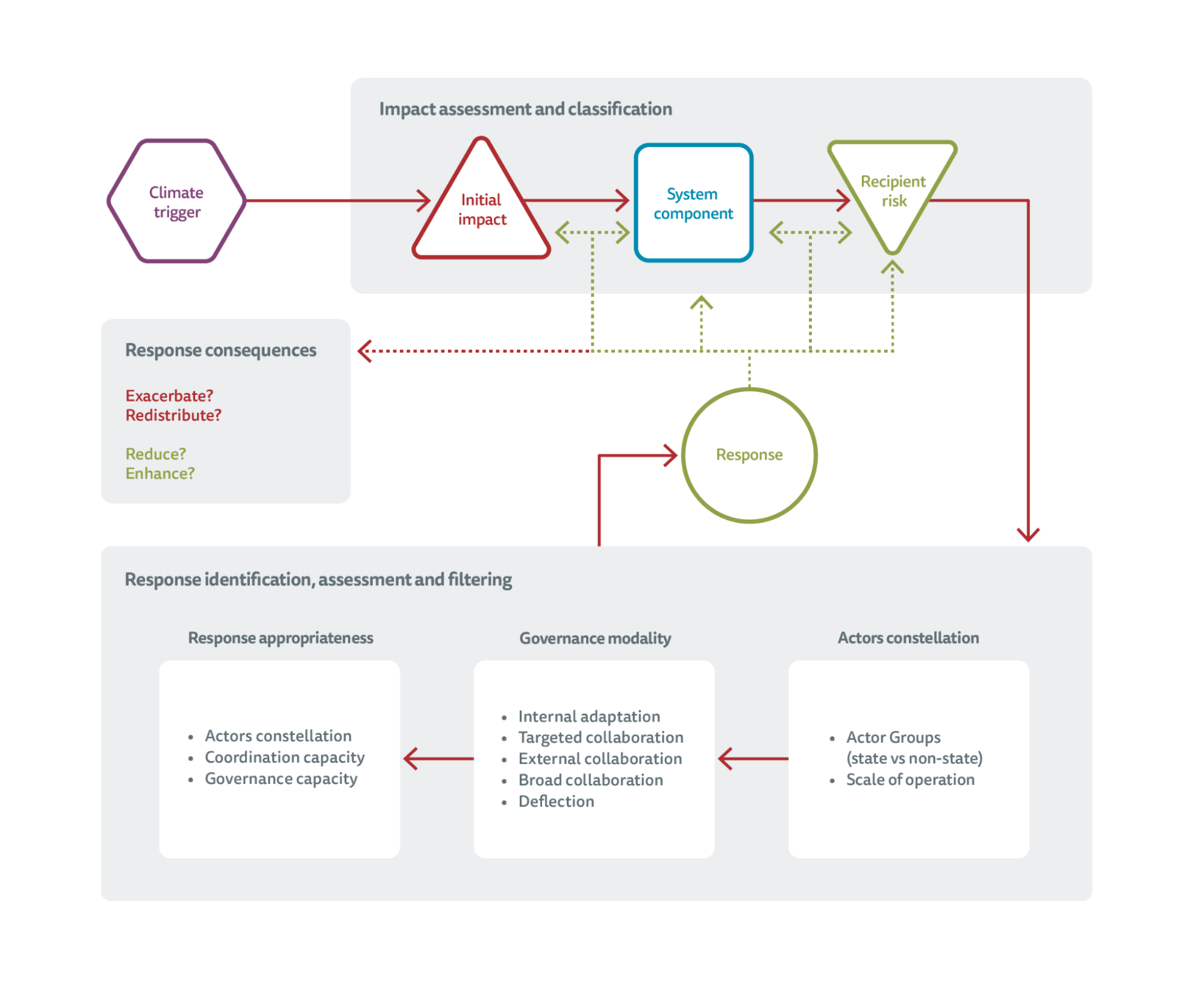

To better understand the appropriate approaches to address cross-border climate impacts within policy realms and design actionable adaptation strategies to respond to associated risks, a response framework (Chapter 1) can help to systematically identify and appraise different types of responses to cross-border climate impacts, covered in more detail in chapter 1. This framework offers a comprehensive process for adaptation planners and policymakers in countries affected by cross-border climate impacts to identify, design, and filter adaptation responses suitable for different systems and levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A conceptual framework for responding to cross-border climate impacts

The response framework focuses on options available to the recipient country. It supports policymakers and adaptation planners in a country at the end of cascading climate risks. The response framework puts forward an impact assessment and classification process as the first step to identify and differentiate between different types of risks. It then offers a response identification, assessment, and filtering process to guide policymakers through selecting suitable policy responses to various types of cross-border climate impacts.

Finally, policymakers are recommended to closely monitor and evaluate response consequences. The response framework recognises that while adaptation responses can reduce vulnerabilities and, in some cases, enhance opportunities for recipient countries, they might also have undesirable consequences and redistribute or exacerbate risks in other locations and countries.

The framework assists adaptation planners and policymakers in identifying suitable intervention points to address cascading climate impacts and anticipate when broad or targeted collaboration with actors across scales and jurisdictions is necessary. It serves to highlight the context in which internal adaptation is suitable and when combining different governance modalities is likely to be necessary and effective.

If the video below does not appear, please accept cookies, or view on YouTube

Key findings by chapter

Chapters 2 until 6 in the report apply the response framework in a light manner, while the last Chapter 7 applies the framework more thoroughly. Each chapter covers different aspects of the response governance framework: different constellations of actors from the national to the regional and international level that collaborate in multiple ways (i.e., bilateral and multilateral collaboration) with affected third countries and other regional and international organisations. The case studies thus demonstrate the diversity of approaches, opportunities and challenges in managing cross-border climate impacts by European actors. Each chapter also ends with concrete policy recommendations for European policymakers and their international partners. Box 1 summarises the main findings of each chapter.

Box 1: Overview of the six case study chapters (Chapters 2 – 7)

|

Chapter 2 finds that the EU’s commitment to supporting adaptation in agri-food systems in North Africa features in the regional strategies and (available) national programmes. However, European adaptation finance to the region is limited. As the EU may mobilise more adaptation-related finance via the Global Gateway initiative or innovative schemes, it will be important to ensure that smallholder farmers can benefit from this type of finance. Lastly, as long as adaptation is not established as a legitimate policy dimension within the EU’s (agri-food) trade policies vis-a-vis North Africa, the EU cannot achieve system-wide adaptation and resilience. Chapter 3, based on a case study of Burkina Faso, finds that a territorial approach that empowers local authorities and involves local communities in resilience-building processes would be a relevant component of a European approach to managing complex cross-border climate risks in the Central Sahel region. Enhancing the management of land and water resources, which are at the centre of inter-communal tensions that have destabilised the countries of this region in the aftermath of climatic shocks, requires legitimate, effective and accountable institutions responding to the needs of local populations and agri-food enterprises. Chapter 4 finds that Germany faces favourable conditions for supporting the climate adaptation of agri-food systems in third countries. That said, there remain several ways in which Germany could make an even stronger contribution, including increasing overall funding, putting a stronger emphasis on climate adaptation (as opposed to mitigation), as well as further advancing the integration of climate action, development cooperation, and security policy and working towards further empowering field staff – in particular in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Chapter 5 finds that Spain’s development cooperation strategy has ‘mainstreaming climate change’ as a priority in its national and international policies. But, its climate-related strategies are outdated. Spain has yet to develop a specific development strategy that fully integrates adaptation to cross-border climate impacts involving agri-food systems. Likewise, it would benefit from a stronger integration of development cooperation instruments and enhanced capacities within the Spanish Agency for International Development Co-operation (AECID) and other relevant institutions to work with various stakeholders. Chapter 6 finds that the EU and its member states are already strong supporters of key international humanitarian organisations working on the agri-food agenda. It also finds that these organisations are already taking action that supports resilience against cross-border climate impacts. But, to achieve system-wide resilience, a greater quantity and quality of financial commitments are necessary. And, there is a need for an increased focus on cross-border climate impacts within existing predictive tools. Chapter 7 highlights that the EU-NATO partnership is centred upon bolstering domestic resilience to climate change and security impacts within EU and NATO member countries. Despite high-level commitments to addressing climate change in 2022, food security has not been given as much attention from both a strategic and operational perspective. Future areas of collaboration between the EU and NATO should include political leadership and climate diplomacy, exchange of best practices and lessons learned, assisting humanitarian aid and disaster relief operations, capacity building in partner countries, and combating disinformation. Jointly, these efforts could move the EU-NATO partnership to more inclusive collaboration to achieve system-wide resilience. |

Main conclusion and strategic challenges to building system-wide resilience

The various contributions in this compilation reveal that there are several ways in which European member states could make a stronger contribution to climate-resilient agri-food systems in third countries and thus shield key foreign policy and development objectives in the European neighbourhood against the adverse effects of climate change. They could increase overall adaptation finance and further advance the mainstreaming of climate adaptation measures into development cooperation and security policy, particularly in fragile contexts. These recommendations are true for Germany and Spain. Empowering field staff in vulnerable partner countries and enhancing capacities to work with a broad range of local and international stakeholders will be helpful. Furthermore, whilst the EU and its member states are among the largest financial backers of the major international humanitarian organisations such as the World Food Programme (WFP), opportunities exist to further improve the quality and availability of this finance for those states facing the most critical agri-food challenges. Furthermore, collaboration with the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) is still centred on the impacts of climate change on defence and military capabilities, but within the context of COVID-19 and the invasion of Ukraine, moving food security further up the agenda for the EU-NATO partnership will be key to avoiding agri-food market disruption and bolstering domestic and regional resilience.

All in all, achieving system-wide adaptation and, ultimately, system-wide resilience requires a level of international cooperation currently missing from European adaptation efforts. Four categories of strategic problems for the EU and its member states to eventually achieve system-wide resilience emerge from the analysis (see figure 2):

- Knowledge of cascading and cross-border climate impacts is still poor. Even less is known about what appropriate tools Europe could use and which measures to take to address them.

- Policy incoherence, affecting adequate adaptation action, remains a strategic problem for Europe.

- Broad multi-level and multi-actor collaboration is missing in Europe,

- Unilaterally closing the adaptation finance gap remains a daunting challenge for Europe.

Figure 2. Strategic challenges for Europe to build system-wide resilience

Therefore, the EU and its member states, individually, collectively and in cooperation with international organisations, could develop, adopt and mainstream better responses and pre-emptive approaches in the four areas of strategic challenges (i.e. knowledge and tools, policies and plans, diplomacy and cooperation, and finance) to minimise cross-border climate impacts. The wide variety of detailed policy recommendations in our compilation will guide the EU in developing a comprehensive strategy for the wider geopolitical impacts of climate change – a challenge may come to dwarf all other international dilemmas in future years.